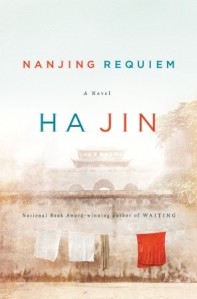

When I learned that the prolific, award-winning Ha Jin had been named to the highly selective American Academy of Arts and Letters (an exclusive honor recognizing only 250 members at any given time), I decided to read Nanjing Requiem (Pantheon, 2011) to learn more about the author and his noted prose style.

When I learned that the prolific, award-winning Ha Jin had been named to the highly selective American Academy of Arts and Letters (an exclusive honor recognizing only 250 members at any given time), I decided to read Nanjing Requiem (Pantheon, 2011) to learn more about the author and his noted prose style.

The central crisis of this historical novel, the so called “Rape of Nanking,” remains one of the most horrific and, simultaneously, under-reported events of the twentieth century. Estimates vary widely (in part, due to few surviving records of the events), but most agree that some 200,000 men were massacred in or around Nanking after the Japanese took the city during the Sino-Japanese War in 1937. Even more startling, Japanese soldiers occupying the city systematically raped more than 20,000 women and children during the atrocity (many of whom were subsequently murdered).

Several heroic figures protected Chinese civilians amidst the genocide, including the American missionary Minnie Vautrin (1886-1941). Vautrin, born in the small town of Secor, Illinois, served as dean of the Jinling Women’s College and protected more than 10,000 women in the college during the tragedy. Although she returned to the U.S. after the events, Vautrin never recovered from the trauma.

Several heroic figures protected Chinese civilians amidst the genocide, including the American missionary Minnie Vautrin (1886-1941). Vautrin, born in the small town of Secor, Illinois, served as dean of the Jinling Women’s College and protected more than 10,000 women in the college during the tragedy. Although she returned to the U.S. after the events, Vautrin never recovered from the trauma.

Nanjing Requiem tells the story of the Japanese occupation by focusing on the actions of Vautrin. When others from the missionary college left the region, Vautrin remained behind to manage the so-called “safety zone,” hoping to make a difference. As thousands of refugees poured into college grounds designed to house only a few hundred, Vautrin mediated between Chinese civilians and Japanese military officials, coordinated relief efforts, and protected the women from the wanton and ever-encroaching soldiers.

Murder, rape, and imprisonment destroy life after life in Nanjing Requiem, but Vautrin is hardly the only heroic figure. Almost lost in the chaos are the unheralded efforts of those women who, harbored by the college, seek information and the release of husbands and sons from prison work camps. Those who survive, men and women alike, live only to face the aftershocks of a blood-soaked land.

Ha Jin’s candid presentation of the genocide has divided readers and critics alike. Some find the author’s sometimes dispassionate style too objective to be fully effective, leaving the psychological depth of central characters under-explored. Others maintain that his literary form necessarily stems from the intensity of his subject matter and the unmistakably horrific nature of crimes committed against young women and children. Marie Arana’s Washington Post review, for example, rightly asks: “How do you fashion art from atrocity? How do you take facts that defy credulity—the slaughter of innocents, the orgies of rape, the lingering stink of a landscape of corpses—and offer them up as an act of the imagination?” This is, after all, a recent, living history—not some wild flight of fancy.

Consider, for example, one scene that occurs immediately after a traumatized girl is taken away by officers for creating a disturbance:

A middle-aged Chinese man held her by the waist from behind, saying, “Please, Principal Vautrin, don’t follow them!” Another few people stepped over to restrain her. A woman began wiping the blood off Minnie’s face with a silk handkerchief.

Minnie stamped her feet, tears flowing down her cheeks while her nose quivered. “Damn you! Damn you, bastards!” she screamed at the backs of the receding policemen. (184)

The passage, representative of the tone of much of the novel, weaves between realism and sentimentality. The scene reveals the height of Minnie’s standing in a community rightly distrustful of outsiders. Her imprecations are audible signs of exhausted emotional resources. Yet Minnie’s interior state remains largely hidden, known through words and actions reported by the narrator alone.

Beyond passing references to Christian missionaries or the Bible, the interior spiritual and psychological motives of different characters are often under-explored. Still, the challenges of prejudice, the complexity of cultural understanding, and the horror of genocide call readers to deeper theological reflection on creation, theological anthropology, and the meaning of community.

The value of all people, each a bearer of the divine image (though not named as such), is revealed through the workers’ goal to count each victim. In the face of genocide, numbers often substituted for naming those who suffered. Names, however, memorialize life. Names reinforce the power of memory, and memory constitutes the abiding value of genealogy.

In Nanjung Requiem, Minnie Vautrin embodies the suffering of so many nameless numbers. Vautrin’s commitment to the people of Nanjing demonstrates what Christians have recognized as the heroic virtue of martyrs and saints. In light of Vautrin’s own decline in the wake of these events, I find it hard to regard her as anything less.

Pingback: Losing Everything: Jenny Offill’s “Dept. of Speculation” | Jeffrey W. Barbeau