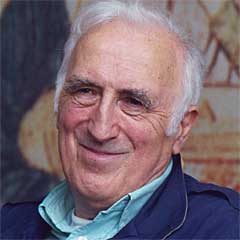

Jean Vanier began a worldwide movement in 1964. While living in northern France, Vanier invited two men, both intellectually disabled, to live with him. In time, what began as a gesture of friendship and hospitality, developed into nearly 150 residential communities around the world. Continue reading

Jean Vanier began a worldwide movement in 1964. While living in northern France, Vanier invited two men, both intellectually disabled, to live with him. In time, what began as a gesture of friendship and hospitality, developed into nearly 150 residential communities around the world. Continue reading

Category Archives: Image of God

Women and Weddings

I’ve always known that John Wesley and (some) Methodists were progressive-thinking folks, but did you know that Wesley’s revision of the marriage rite helped advance the state of women? Continue reading

Niffenegger’s Raven Girl and the Image of God

Twice, in the short life of this blog, I have written on Audrey Niffenegger’s synthesis of visual and poetic arts. The Night Bookmobile—a terrifying exploration of the “dark side of reading”—first captured my attention. Later, I compared her work to William Blake in the imaginative The Adventuress and The Three Incestuous Sisters, describing her creations as “stories of anger, resentment, love, longing, loss, and escape . . . morality tales of transformation embodied in the strange and paranormal.”

Twice, in the short life of this blog, I have written on Audrey Niffenegger’s synthesis of visual and poetic arts. The Night Bookmobile—a terrifying exploration of the “dark side of reading”—first captured my attention. Later, I compared her work to William Blake in the imaginative The Adventuress and The Three Incestuous Sisters, describing her creations as “stories of anger, resentment, love, longing, loss, and escape . . . morality tales of transformation embodied in the strange and paranormal.”

Her latest graphic novella, Raven Girl (Abrams ComicArts, 2013) continues to shape Niffenegger’s growing reputation as a leading figure in contemporary storytelling. The book originated in a request from the Royal Ballet for a “dark” tale to be developed for production. A fairy tale at heart, Raven Girl follows a postman who falls in love with a raven (an intriguing reversal of Coleridge’s Mariner & Albatross). The two eventually have a child—a raven girl. She looks like a girl, that is, but her skeletal and other biological systems have some features that are more bird than human. She cannot speak human languages, but neither can she fly. Raven Girl is an exploration of the bodily dysphoria the girl experiences and the quest to attain functional wings of her own.

Among several themes raised in the story, Niffenegger’s work encourages reflection on the meaning of the image of God in the person. Through the voice of an antagonist—a young man who falls in love with the raven girl, only to violently oppose her efforts to change her body through surgery—Niffenegger challenges the belief that our bodies should be treated as immutable, in some sense, due to their creation in the divine image.

Among several themes raised in the story, Niffenegger’s work encourages reflection on the meaning of the image of God in the person. Through the voice of an antagonist—a young man who falls in love with the raven girl, only to violently oppose her efforts to change her body through surgery—Niffenegger challenges the belief that our bodies should be treated as immutable, in some sense, due to their creation in the divine image.

Readers of Raven Girl who reduce the story to a simplistic morality play of contemporary bioethics, however, may fail to see other opportunities for literary and theological reflection. While the tale invokes a discussion of body and identity, Raven Girl also encourages meditation on the relationship between the divine image and creation as a whole.

Raven Girl is, in many ways, a tragic story of isolation and estrangement—from the self and others. The postman and raven fall in love, but they do so while experiencing, to varying degrees, alienation from their respective communities. The raven girl, though surrounded by other children, grows up without friends and others who nurture, shape, and care for her development. Loneliness, isolation, and longing surround these characters, even amidst moments of tranquility and joy.

While the bodily dimension of the story deserves our attention—our bodies, and what we do with them, matter—readers should attend to the social dimension of the story, too. True humanity is discovered in the demonstration of love—the love of God, neighbor, and all creation. In fact, Raven Girl unexpectedly affirms the deeply Christian belief in created relationality in its final pages. The love of the raven prince who seeks out the mysterious girl affirms a wider vision of reconciliation, community, and restorative relationships. Through their love, the enmity between alienated beings is put to rights.