My fascination with Audrey Niffenegger’s graphic novel The Night Bookmobile (2010) inspired a search for more of the Chicago-based artist’s works. While her acclaimed debut novel The Time Traveler’s Wife (2003) didn’t capture my interest (I confess I made it only a third of the way into the book), two of her graphic novels merit further notice.

Niffenegger’s The Three Incestuous Sisters (2005) and The Adventuress (2006) require a different kind of reader—the kind I long to be; the kind I encourage my students to become.

Niffenegger’s The Three Incestuous Sisters (2005) and The Adventuress (2006) require a different kind of reader—the kind I long to be; the kind I encourage my students to become.

Niffenegger compares her work to “a silent film made from Japanese prints . . . a silent opera” (“Afterword,” The Three Incestuous Sisters). The artist’s words are few. Language tells one part of the story. Niffenegger’s beautiful and haunting—even nightmarish—images complete the narrative. In these stories, images convey meaning beyond language, calling imagination to furnish the tale’s complex struggle with beliefs, motives, and action captured still-frame in nitric acid baths.

The “Afterword” of TIS describes Niffenegger’s laborious process of discovery: “The Three Incestuous Sisters’s first incarnation was an artist’s book, in a handmade edition of ten. I created the story in pictures, sketching page spreads the way a director might work out the storyboard for a film. I wrote the text; as the images gained in complexity, the text dwindled until the weight of the story was carried by the images. I then spent most of the next thirteen years making the aquatints, designing the book, and setting and printing the type. The final year of the project was spent binding the books, elaborately, in leather” (“Afterword”).

The “Afterword” of TIS describes Niffenegger’s laborious process of discovery: “The Three Incestuous Sisters’s first incarnation was an artist’s book, in a handmade edition of ten. I created the story in pictures, sketching page spreads the way a director might work out the storyboard for a film. I wrote the text; as the images gained in complexity, the text dwindled until the weight of the story was carried by the images. I then spent most of the next thirteen years making the aquatints, designing the book, and setting and printing the type. The final year of the project was spent binding the books, elaborately, in leather” (“Afterword”).

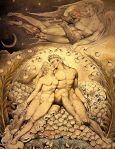

Since the time I first sat down with these two works, I have been reminded of William Blake’s unique etchings. Blake’s melding of image and poetry remain among the most stimulating creative accomplishments of British Romantic literature. Time will tell if Niffenegger will continue to pursue this seemingly less-profitable form of creation (given the success of The Time Traveler’s Wife), but the two artists share a common concern for the unique materiality of their works. Niffenegger explains, “I make books because I love them as objects; because I want to put the pictures and words together, because I want to tell a story” (“Afterword”).

Since the time I first sat down with these two works, I have been reminded of William Blake’s unique etchings. Blake’s melding of image and poetry remain among the most stimulating creative accomplishments of British Romantic literature. Time will tell if Niffenegger will continue to pursue this seemingly less-profitable form of creation (given the success of The Time Traveler’s Wife), but the two artists share a common concern for the unique materiality of their works. Niffenegger explains, “I make books because I love them as objects; because I want to put the pictures and words together, because I want to tell a story” (“Afterword”).

The result is beautiful. These are stories of anger, resentment, love, longing, loss, and escape. They are, in very different ways, morality tales of transformation embodied in the strange and paranormal.

Stories such as these can be consumed in less than an hour. The creative process advanced slowly over the course of years. Meaning emerges in the meditation and reflection in-between.

Romantic narrative of the solitary wanderer. As the story goes, the poet-genius rambles off into the woods or high up along the ridge of a mountain and, along the way, encounters the divine.

Romantic narrative of the solitary wanderer. As the story goes, the poet-genius rambles off into the woods or high up along the ridge of a mountain and, along the way, encounters the divine.