What does it feel like to lose what matters most? It feels like life is askant, disoriented, even though you are surrounded by friends, children, and meaningful work. That’s why Jenny Offill’s Dept of Speculation (Vintage, 2014) works. Continue reading

What does it feel like to lose what matters most? It feels like life is askant, disoriented, even though you are surrounded by friends, children, and meaningful work. That’s why Jenny Offill’s Dept of Speculation (Vintage, 2014) works. Continue reading

Category Archives: Literature

Paul Fiddes on Theology and Literature

I recently shared a passage from Paul Fiddes’s The Promised End: Eschatology in Theology and Literature (2000) with students in my class on interdisciplinary theology. Fiddes, Professor of Systematic Theology at the University of Oxford, offers a constructive model for how to perform theology through literature: Continue reading

I recently shared a passage from Paul Fiddes’s The Promised End: Eschatology in Theology and Literature (2000) with students in my class on interdisciplinary theology. Fiddes, Professor of Systematic Theology at the University of Oxford, offers a constructive model for how to perform theology through literature: Continue reading

Romanticism and Materialism in Thelwall

Romanticism can be linked with vitalism, idealism, and varieties of anti-materialism, but the period also gives evidence to other philosophical and scientific conceptions of the world. Yasmin Solomonescu’s John Thelwall and the Materialist Imagination (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) provides an intriguing new account of how Thelwall intended to produce “material effects on the minds and bodies of audiences in the service of sociopolitical reform” (7). Solomonescu uses the term “materialist” to convey more than a natural philosophy by extending scientific materialism to political and social life broadly conceived. Continue reading

Romanticism can be linked with vitalism, idealism, and varieties of anti-materialism, but the period also gives evidence to other philosophical and scientific conceptions of the world. Yasmin Solomonescu’s John Thelwall and the Materialist Imagination (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) provides an intriguing new account of how Thelwall intended to produce “material effects on the minds and bodies of audiences in the service of sociopolitical reform” (7). Solomonescu uses the term “materialist” to convey more than a natural philosophy by extending scientific materialism to political and social life broadly conceived. Continue reading

Blake and Methodism

William Blake’s religious thought is notoriously challenging. Several recent studies, however, shed light on this area through particular attention to the theological and historical impact of British Methodism on his achievement. Two recent monographs deserve mention.

Jennifer Jesse, in William Blake’s Religious Vision: There’s a Methodism in His Madness (Lanham: Lexington, 2013), maintains that Blake works “against the backdrop” of Wesleyan theology. She argues that Blake critics have relied excessively on contemporary caricatures of the Wesleys, Whitefield, and Methodism generally rather than historically accurate portrayals of the movement. Continue reading

Jennifer Jesse, in William Blake’s Religious Vision: There’s a Methodism in His Madness (Lanham: Lexington, 2013), maintains that Blake works “against the backdrop” of Wesleyan theology. She argues that Blake critics have relied excessively on contemporary caricatures of the Wesleys, Whitefield, and Methodism generally rather than historically accurate portrayals of the movement. Continue reading

Romanticism and Islam

One of the intriguing new developments in British Romantic studies centers on the religious sources of the poets, particularly the Arabic-Islamic sources that proved decisive influences on some of the most remarkable poetic works in the English language. Samar Attar’s fascinating new book, Borrowed Imagination: The British Romantic Poets and the Arabic-Islamic Sources (Lexington, 2014) builds on positive scholarly contributions by Nigel Leask, Gregory Wassil, and Emily Haddad. Continue reading

One of the intriguing new developments in British Romantic studies centers on the religious sources of the poets, particularly the Arabic-Islamic sources that proved decisive influences on some of the most remarkable poetic works in the English language. Samar Attar’s fascinating new book, Borrowed Imagination: The British Romantic Poets and the Arabic-Islamic Sources (Lexington, 2014) builds on positive scholarly contributions by Nigel Leask, Gregory Wassil, and Emily Haddad. Continue reading

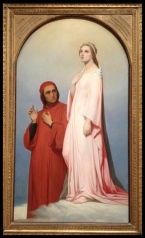

From Beatrice to Romanticism

My family named our new puppy Beatrice. Not after “Tris” of Divergent fame, but after Beatrice Portinari—Dante’s inspiration and the celestial muse of The Divine Comedy.

My family named our new puppy Beatrice. Not after “Tris” of Divergent fame, but after Beatrice Portinari—Dante’s inspiration and the celestial muse of The Divine Comedy.

I was an undergraduate when I first read Dante with delight, but in my subsequent study of Romanticism I found that Dante was also a favorite in the nineteenth century. Continue reading

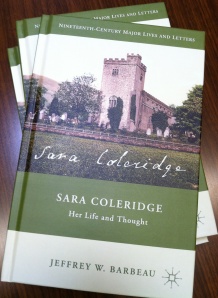

For My Children

From my new book, Sara Coleridge: Her Life and Thought, now in print. The first lines I shared were with my children, which I print here for all to read: Continue reading

From my new book, Sara Coleridge: Her Life and Thought, now in print. The first lines I shared were with my children, which I print here for all to read: Continue reading

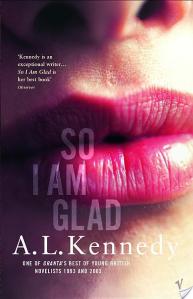

Confused by A. L. Kennedy

Funny how words and sentences and language work. The title to this post could mean at least two things:

Funny how words and sentences and language work. The title to this post could mean at least two things:

1. The ingenious Scottish novelist A. L. Kennedy wrote a new book titled Confused.

2. The ingenious Scottish novelist A. L. Kennedy writes in such a way that many readers are confused.

See how troubling this is? Since I enjoyed Kennedy’s dark, alcohol-fueled dream Paradise, I thought I’d give the critically-acclaimed So I Am Glad (Knopf, 1995) a shot (that’s right: #1, above, is false).

The narrator of So I Am Glad, Jenny, is a young woman who risks love by way of a mysterious man (“Martin”) who turns up in her flat. Along the way we learn about Jenny’s traumatic childhood, an abusive relationship with her ex-boyfriend, and her rather antiseptic occupation as an audio narrator. Throughout, the novel induces a state of bewilderment: the character dialogue is as pedestrian, random, and spasmodic as most conversations of everyday life, and even when Martin’s true identity is revealed, the reader remains uncertain and distrustful to the end.

Kennedy’s works are artful—brilliantly constructed—but certainly not for everyone.

Suffice it to say that when I finished the book I took a spin over to Goodreads—just to see what other readers thought. I quickly discovered that I am:

1. One of the few readers on the site to pick up the book and actually finish it.

2. One of the many readers on the site to find Kennedy’s whiplash dialogue construction confusing (there are few identifying references to guide readers, e.g. “said Martin,” “I stammered,” “he shouted,” etc.).

With reference to #1, I rarely fail to finish books I start reading. I also clean my dinner plate, watch through the end of the credits of most movies, and hate it when baseball games are called due to rain or darkness. I prefer to think of this as a virtue rather than a vice. Let’s call it faithfulness; the challenge keeps me going.

With reference to #2, I admit I had to reread the first thirty or forty pages of So I Am Glad more than once to make sure I was tracking the dialogue. Three times, actually. I suppose it’s a badge of honor that I eventually came to understand and even appreciate this rather depressing (and sometimes quite violent) fantasy of love and coming-to-terms-with-the-past novel. Reading this work helped me to see a development in Kennedy’s style that made me appreciate the stream-of-consciousness construction of Paradise all the more.

So I Am Glad . . . Sure I was confused, but you knew that by the name of this post, didn’t you?

Paradise and Desire

A. L. Kennedy’s Paradise (Knopf, 2004) explores the tragic descent of Hannah Luckraft, an alcoholic. Several critics have interpreted Paradise through the stations of the cross. I find this reading quite compelling—its fourteen parts may indeed parallel the Via Dolorosa. For me, however, Kennedy’s narrative describes something much closer to home—what few religious texts ever manage to convey within the limits of philosophical and theological discourse: a complex portrait of the individual will enslaved by desire.

A. L. Kennedy’s Paradise (Knopf, 2004) explores the tragic descent of Hannah Luckraft, an alcoholic. Several critics have interpreted Paradise through the stations of the cross. I find this reading quite compelling—its fourteen parts may indeed parallel the Via Dolorosa. For me, however, Kennedy’s narrative describes something much closer to home—what few religious texts ever manage to convey within the limits of philosophical and theological discourse: a complex portrait of the individual will enslaved by desire.

Paradise requires the reader to explore the dark recesses of the soul through its train-wreck central character, Hannah. Existential confusion and sensory overload pervade the book: “He gets me another whisky and then one of its relatives, and then one of its friends and I should be drunk by now, I should be feeling it, I should—in the absence of other pleasures—be in my house with the whole whisky family, all of us curled up tight around our fine, warm, cask-matured, internal fire. But I’m not. I am entirely sober. I can hear owls snatching mice in the park behind us . . . My skin is unbearable, it is holding me back, holding me in and the shine of his body is hurting it, turning so intense that I ought to be seeing blisters rise and he’s so far away across the table and talking about I have no idea what—he’s too close to hear, drowned out by the babies crying across the river and changing their minds and dreaming, dreaming loud as hand grenades—and why is he so warm when I can’t touch him?” (44).

Kennedy has a knack for describing sensory experience. The effect is profound and brings to mind one of the darkest portraits of the self in Western literature. Augustine famously wrote of the consuming power of self in Confessions—“It was foul, and I loved it. I loved my own undoing. I loved my error—not that for which I erred but the error itself” (Book 2.4).

Augustine’s account of the soul enslaved by sin, however, differs considerably from Kennedy’s Paradise. While Augustine found redemption in the spoken words of a child, Tolle lege, tolle, lege (“Take and read; take and read”), Hannah’s journey entails a cycle of devolution. Despair alone remains.

As any reader of Dante knows, this is no Paradise. It is Inferno.

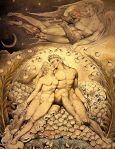

Echoes of William Blake

My fascination with Audrey Niffenegger’s graphic novel The Night Bookmobile (2010) inspired a search for more of the Chicago-based artist’s works. While her acclaimed debut novel The Time Traveler’s Wife (2003) didn’t capture my interest (I confess I made it only a third of the way into the book), two of her graphic novels merit further notice.

Niffenegger’s The Three Incestuous Sisters (2005) and The Adventuress (2006) require a different kind of reader—the kind I long to be; the kind I encourage my students to become.

Niffenegger’s The Three Incestuous Sisters (2005) and The Adventuress (2006) require a different kind of reader—the kind I long to be; the kind I encourage my students to become.

Niffenegger compares her work to “a silent film made from Japanese prints . . . a silent opera” (“Afterword,” The Three Incestuous Sisters). The artist’s words are few. Language tells one part of the story. Niffenegger’s beautiful and haunting—even nightmarish—images complete the narrative. In these stories, images convey meaning beyond language, calling imagination to furnish the tale’s complex struggle with beliefs, motives, and action captured still-frame in nitric acid baths.

The “Afterword” of TIS describes Niffenegger’s laborious process of discovery: “The Three Incestuous Sisters’s first incarnation was an artist’s book, in a handmade edition of ten. I created the story in pictures, sketching page spreads the way a director might work out the storyboard for a film. I wrote the text; as the images gained in complexity, the text dwindled until the weight of the story was carried by the images. I then spent most of the next thirteen years making the aquatints, designing the book, and setting and printing the type. The final year of the project was spent binding the books, elaborately, in leather” (“Afterword”).

The “Afterword” of TIS describes Niffenegger’s laborious process of discovery: “The Three Incestuous Sisters’s first incarnation was an artist’s book, in a handmade edition of ten. I created the story in pictures, sketching page spreads the way a director might work out the storyboard for a film. I wrote the text; as the images gained in complexity, the text dwindled until the weight of the story was carried by the images. I then spent most of the next thirteen years making the aquatints, designing the book, and setting and printing the type. The final year of the project was spent binding the books, elaborately, in leather” (“Afterword”).

Since the time I first sat down with these two works, I have been reminded of William Blake’s unique etchings. Blake’s melding of image and poetry remain among the most stimulating creative accomplishments of British Romantic literature. Time will tell if Niffenegger will continue to pursue this seemingly less-profitable form of creation (given the success of The Time Traveler’s Wife), but the two artists share a common concern for the unique materiality of their works. Niffenegger explains, “I make books because I love them as objects; because I want to put the pictures and words together, because I want to tell a story” (“Afterword”).

Since the time I first sat down with these two works, I have been reminded of William Blake’s unique etchings. Blake’s melding of image and poetry remain among the most stimulating creative accomplishments of British Romantic literature. Time will tell if Niffenegger will continue to pursue this seemingly less-profitable form of creation (given the success of The Time Traveler’s Wife), but the two artists share a common concern for the unique materiality of their works. Niffenegger explains, “I make books because I love them as objects; because I want to put the pictures and words together, because I want to tell a story” (“Afterword”).

The result is beautiful. These are stories of anger, resentment, love, longing, loss, and escape. They are, in very different ways, morality tales of transformation embodied in the strange and paranormal.

Stories such as these can be consumed in less than an hour. The creative process advanced slowly over the course of years. Meaning emerges in the meditation and reflection in-between.