I recently shared a passage from Paul Fiddes’s The Promised End: Eschatology in Theology and Literature (2000) with students in my class on interdisciplinary theology. Fiddes, Professor of Systematic Theology at the University of Oxford, offers a constructive model for how to perform theology through literature: Continue reading

I recently shared a passage from Paul Fiddes’s The Promised End: Eschatology in Theology and Literature (2000) with students in my class on interdisciplinary theology. Fiddes, Professor of Systematic Theology at the University of Oxford, offers a constructive model for how to perform theology through literature: Continue reading

Category Archives: Theology

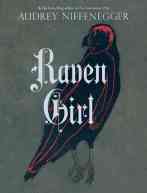

Niffenegger’s Raven Girl and the Image of God

Twice, in the short life of this blog, I have written on Audrey Niffenegger’s synthesis of visual and poetic arts. The Night Bookmobile—a terrifying exploration of the “dark side of reading”—first captured my attention. Later, I compared her work to William Blake in the imaginative The Adventuress and The Three Incestuous Sisters, describing her creations as “stories of anger, resentment, love, longing, loss, and escape . . . morality tales of transformation embodied in the strange and paranormal.”

Twice, in the short life of this blog, I have written on Audrey Niffenegger’s synthesis of visual and poetic arts. The Night Bookmobile—a terrifying exploration of the “dark side of reading”—first captured my attention. Later, I compared her work to William Blake in the imaginative The Adventuress and The Three Incestuous Sisters, describing her creations as “stories of anger, resentment, love, longing, loss, and escape . . . morality tales of transformation embodied in the strange and paranormal.”

Her latest graphic novella, Raven Girl (Abrams ComicArts, 2013) continues to shape Niffenegger’s growing reputation as a leading figure in contemporary storytelling. The book originated in a request from the Royal Ballet for a “dark” tale to be developed for production. A fairy tale at heart, Raven Girl follows a postman who falls in love with a raven (an intriguing reversal of Coleridge’s Mariner & Albatross). The two eventually have a child—a raven girl. She looks like a girl, that is, but her skeletal and other biological systems have some features that are more bird than human. She cannot speak human languages, but neither can she fly. Raven Girl is an exploration of the bodily dysphoria the girl experiences and the quest to attain functional wings of her own.

Among several themes raised in the story, Niffenegger’s work encourages reflection on the meaning of the image of God in the person. Through the voice of an antagonist—a young man who falls in love with the raven girl, only to violently oppose her efforts to change her body through surgery—Niffenegger challenges the belief that our bodies should be treated as immutable, in some sense, due to their creation in the divine image.

Among several themes raised in the story, Niffenegger’s work encourages reflection on the meaning of the image of God in the person. Through the voice of an antagonist—a young man who falls in love with the raven girl, only to violently oppose her efforts to change her body through surgery—Niffenegger challenges the belief that our bodies should be treated as immutable, in some sense, due to their creation in the divine image.

Readers of Raven Girl who reduce the story to a simplistic morality play of contemporary bioethics, however, may fail to see other opportunities for literary and theological reflection. While the tale invokes a discussion of body and identity, Raven Girl also encourages meditation on the relationship between the divine image and creation as a whole.

Raven Girl is, in many ways, a tragic story of isolation and estrangement—from the self and others. The postman and raven fall in love, but they do so while experiencing, to varying degrees, alienation from their respective communities. The raven girl, though surrounded by other children, grows up without friends and others who nurture, shape, and care for her development. Loneliness, isolation, and longing surround these characters, even amidst moments of tranquility and joy.

While the bodily dimension of the story deserves our attention—our bodies, and what we do with them, matter—readers should attend to the social dimension of the story, too. True humanity is discovered in the demonstration of love—the love of God, neighbor, and all creation. In fact, Raven Girl unexpectedly affirms the deeply Christian belief in created relationality in its final pages. The love of the raven prince who seeks out the mysterious girl affirms a wider vision of reconciliation, community, and restorative relationships. Through their love, the enmity between alienated beings is put to rights.

Christianity and Violence

The United States faces a unique problem: unparalleled violence among developed nations. While American Christians widely repudiate violence, the slaughter of innocents, and the abuse of power, many also assert the inviolability of individual rights involving potentially violent acts—especially regarding restrictions on assault weapons. No small part of the varied Christian responses to violence stems from cultural location. Traditions (even, or perhaps especially, political ones) shape Christian self-understanding.

This raises a fundamental question: How can Christians initiate change in the American culture of violence when so many Christians are unable to agree on the nature of the problem?

Consider Jacques Ellul’s provocative assessment of American history in Violence: Reflections from a Christian Perspective (New York, 1969):

“Americans have it that the Civil War was an accidental interruption of what was practically an idyllic state of affairs; actually, that war simply tore the veil off reality for a moment . . . Tocqueville saw the facts clearly. He indicated all the factors showing that the United States was in a situation of violence which, he predicted, would worsen. As a matter of fact, a tradition of violence is discernible throughout United States history—perhaps because it is a young nation, perhaps because it plunged into the industrial age without preparation. (This tradition, incidentally, explains the popularity of violence in the movies.) And it seems that the harsher and more violent the reality was, the more forcefully were moralism and idealism affirmed” (88–89).

Ellul traces the American culture of violence not to slavery or the civil war, but “the slow, sanctimonious extermination” of Native Americans, the competitive methods of capitalism, and the annexation of land in Texas and California. “All this,” he explains, “and much besides show that the United States has always been ridden by violence, though the truth was covered over by a legalistic ideology and a moralistic Christianity” (88).

Violence permeates the fabric of American culture. The problem, however, as recent events have shown, is not a matter of international war or the abuse of governmental authority alone. Many Christians, far from denouncing the culture of violence, willingly embrace the principle of “an eye for an eye” as the solution to the problem. Instead of repudiating the culture of violence, we often assert an illusory notion of individualism and justice based on the primacy of the self.

I am not suggesting that there is no place for national defense, local government, or individual participation in the political sphere. American sports involve violence, too, and I remain uncertain how to assess that aspect of the larger problem. The task, in short, is immense.

Let’s be clear: Violence may sometimes be deemed necessary, but it is certainly not a Christian value. Violence stands outside of the freedom found in Jesus Christ—the one who bore the violence of the world for our redemption. Violence is marked by fear, doubt, and unbelief. Violence reminds us of the brokenness of our world. Violence demands repentance.

Christians must challenge the churches to reexamine pervasive cultural assumptions. The causes of violence in American society are undoubtedly complex, and it is tempting to assert that there is no viable solution to the problem. Christians will continue to disagree on the best political methods to curb violence in our nation, but the ability to see the face of violence in our nation requires courage acquired “through faith and hope in Jesus Christ” (Ellul, 91).

American Christians must find the courage to reject the instinctual appeal to violence. Violence belongs to the Fall, to the curse of sin, and to a world separated from God. While perfect peace belongs to the eschaton, Christians who follow in the path of Christ must discover—through fellowship and proclamation—the promised hope found in Christ.

The culture of violence in America will not change in a moment, a decade, or even, perhaps, in a lifetime. Christians are called to lead their communities in acts of reconciliation, even at the expense of self-interest and the risk of individual well-being. Those who profess to follow the way of Jesus Christ ought to renounce the temptation to take up any other means to solve those ills that face us, and determine instead to know only love in word and deed until “they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning-hooks; nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore” (Isa. 2:4).

Don’t Throw Away Your Hymnals!

Epiphany is this coming Sunday, so Christmas isn’t over yet.

In the days leading up to Christmas, I saw quite a few friends posting a link to Peter Leithart’s fascinating blog: “How N. T. Wright Stole Christmas.” Leithart is an excellent scholar—I frequently find myself turning to his works on early Christianity—but something seemed missing in his interpretation of Christmas hymns. How could Isaac Watts, Charles Wesley, and John Keble be so misguided?

In the days leading up to Christmas, I saw quite a few friends posting a link to Peter Leithart’s fascinating blog: “How N. T. Wright Stole Christmas.” Leithart is an excellent scholar—I frequently find myself turning to his works on early Christianity—but something seemed missing in his interpretation of Christmas hymns. How could Isaac Watts, Charles Wesley, and John Keble be so misguided?

I wrote up a response, which appeared on First Things as “Don’t Let N. T. Wright Steal Christmas.”

If you missed my blog over the winter break or didn’t have time to respond, I hope you’ll take a moment to read it and share your thoughts.

Merry Christmas!